Cardiovascular

Effect of educational intervention on risk factors of cardiovascular diseases among school teachers: a quasi-experimental study in a suburb of Kolkata, West Bengal, India

Participants

This multicentric quasi-experimental study took place from August 2016 to May 2017 among teachers in four schools in Baruipur, a Kolkata suburb, West Bengal, India. We used simple random sampling (SRS) with replacement to select four clusters out of 18 in the Baruipur block, each containing an average of 18.5 ~ 19 schools. From each cluster, one school was chosen [13].

After securing permission and informed written consent from school heads, all teachers working in the study schools during baseline assessments were included. The four study schools were then randomly assigned to either the intervention or control group. Sample sizes were determined based on parameters from a similar study by Awosan et al. [12] in Nigeria since there were no prior Indian studies available. For systolic blood pressure (SBP), we estimated a mean difference of 2.87 with a standard deviation of 9.2, requiring a sample size of 66 per arm for 80% power and a 5% significance level. Similarly, for fasting blood sugar (FBS) and total blood cholesterol, sample sizes of 17 in each arm were calculated to detect differences of 6.69 mg/dl and 12.71 mg/dl, respectively, with their respective standard deviations [12]. We used the online sample size calculator Statulator [14] for these calculations.

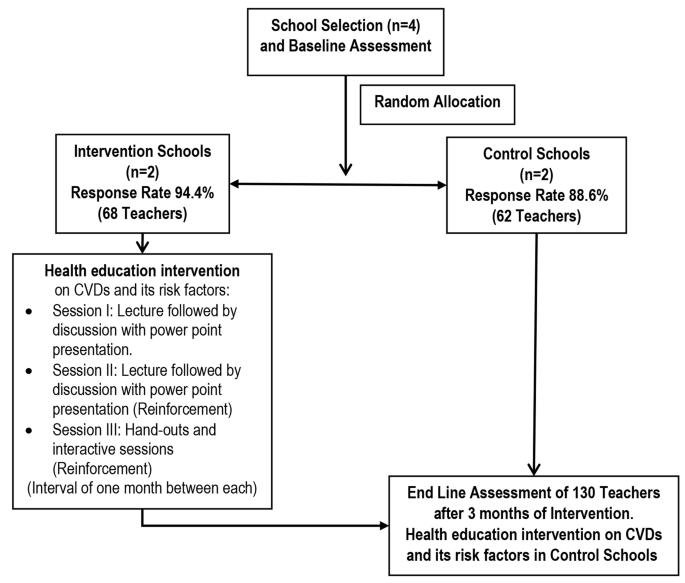

The study enrolled 68 teachers in the intervention group and 62 in the control group, totalling 130 participants. Data collection schedules were coordinated with school authorities. We utilized a pre-designed, pretested, self-administered questionnaire, clinical examination, and laboratory blood investigations. Blood pressure and anthropometric measurements adhered to standard operating procedures. Female teachers received examinations with a female attendant to ensure privacy. Teachers arrived at school one hour before classes, following a 12-hour fasting period, for blood sample collection.

Intervention

We created an educational module covering key aspects of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs): common types, modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors, prevention, diabetes and obesity complications, and guidance on healthy diet, physical activity, stress management, and quitting addictions. This module adhered to guidelines from the National Institute of Nutrition, Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), and the World Health Organization (WHO) [15, 16]. We also prepared PowerPoint presentations (Annexure I) to enhance interactive lectures.

We conducted intervention sessions, approved by the Teacher-in-charge, in the teachers’ room or school auditorium using a laptop and projector, held on Saturdays after school hours without disrupting regular academic activities. We reinforced learning by repeating lectures twice per school with a one-month gap between. Interactive sessions addressed questions and clarified content. Handouts (Annexure II) aided retention. Three months post-intervention, we conducted an endline assessment using the same tools as the baseline, excluding background characteristics. Control schools received subsequent intervention sessions. Figure 1 illustrates the study processes.

Flowchart indicating the study process

Measures

Behavioural characteristics

Physical activity levels were assessed using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF), with individuals reporting ≥ 600 metabolic equivalent (MET) per week classified as physically active [17, 18]. Meeting the recommended salt intake of < 5 g per day and consuming < 500 ml of oil per month aligned with guidelines [16, 19]. Meeting the recommendation for fruit and vegetable consumption meant consuming ≥ 400 g daily [19]. Tobacco users were defined as those reporting tobacco use in the past 30 days [20]. Stress levels were measured using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), consisting of four items, with higher scores indicating increased stress levels [21].

Biological characteristics

We adhered to standard operating procedures for measuring blood pressure, height, weight, waist circumference, and hip circumference. Fasting blood sugar (FBS) and lipid profiles, including total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and triglycerides, were assessed using established protocols [19, 20]. Individuals taking antihypertensive medication or with systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 90 mm Hg were classified as hypertensive. Those on antidiabetic medication or with FBS ≥ 126 mg/dl were considered diabetic. Obesity was defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m², and central obesity as waist circumference > 80 cm for females and > 90 cm for males. A waist-hip ratio > 0.85 for females and > 90 cm for males indicated a higher risk.

Cardiovascular risk scores

We identified a higher risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) as total cholesterol levels ≥ 200 mg/dl, LDL ≥ 130 mg/dl, and triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dl, while a cardioprotective HDL level was defined as < 50 mg/dl for women and < 40 mg/dl for men [15, 19, 20, 22]. We calculated the Framingham 10-year cardiovascular risk score using age, sex, total and HDL cholesterol, smoking status, and blood pressure, following established calculation guidelines [23, 24]. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome was determined according to the new International Diabetes Federation (IDF) definitions [25].

Statistical analysis plan

We conducted data analysis using JAMOVI (version 2.3.26), an open-source statistical software [26]. Initially, we inputted the data into Microsoft Excel and then imported it into JAMOVI for analysis. Descriptive statistics included reporting quantitative and qualitative variables, using frequency (percentage) and median [interquartile range (IQR)]. To compare baseline and endline behavioural and biological characteristics related to cardiovascular health between the intervention and control groups, we employed the Mann-Whitney U test for qualitative variables and the Chi-square test for quantitative variables. Within each group, we used the Wilcoxon matched pair signed rank test for qualitative variables and McNemar’s test for quantitative variables to compare baseline and endline characteristics. We measured the effect size using Cohen’s D. In all quantitative analyses, a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, indicating significant differences between groups or within groups over time.