Cardiovascular

New CVD Risk Equations are Sex-Specific, Exclude Race, Include eGFR, and Predict Heart Failure

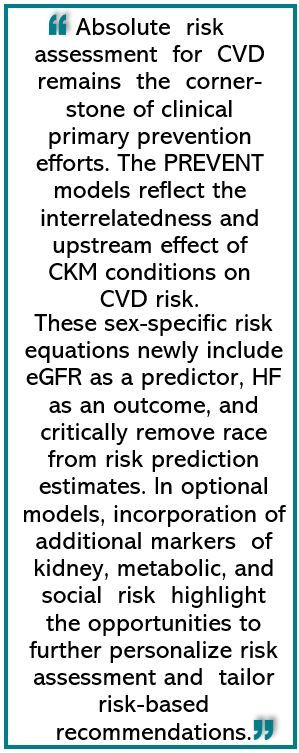

A revised cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk calculator published by the American Heart Association (AHA) now accounts for a full spectrum of risk factors that contribute to increasing rates of CVD morbidity and mortality. The PREVENT (Predicting Risk of cardiovascular disease EVENTs) calculator retains the use of traditional health metrics and also incorporates, for the first time, measures of kidney and metabolic disease, including type 2 diabetes and obesity.1The tool is designed to estimate both 10- and 30-year risk of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and, also for the first time, heart failure (HF) for a broad population of individuals.1

PREVENT was introduced on November 10 in a scientific statement published in the journal Circulation, along with a methods paper detailing the development and testing of the new calculator and the new formulas.2

The equations in the PREVENT tool can be used to estimate risk in persons as young as age 30 years, 10 years earlier than the current guideline-recommended calculator; they introduce sex-specific evaluations, recognizing the unique factors that predispose women to heart disease, and omit considerations of race in predicting future disease, acknowledging it as a social factor and not a biological variable germane to predicting CVD risk.1 PREVENT has an option to include an index when appropriate that incorporates social determinants of health into assessment of risk, including socioeconomic factors, educational background, physical environment, and health care access.3

The equations in the PRVENT tool…omit considerations of race in predicting future disease, acknowledging it as a social factor and not a biological variable germane to predicting CVD risk.

PREVENT risk calculations account for the myriad advances in disease knowledge and rapid increase in options for pharmacotherapy since the publication in 2013 of the Pooled Cohort Equations (PCE) by the American College of Cardiology/AHA.

Further, “The Pooled Cohort Equations were developed with data from only white and Black adults and had separate equations for people of each race,” Sadiya S Khan, MD, MSc, chair of the statement writing committee for the Association, said in an AHA statement.1 “There was not a risk model for individuals from other race and ethnicity groups, so we likely were not accurately estimating risk in many people.”1

Khan called the new equations “a critical first step toward including CKM [cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic] health and social factors in risk prediction” for cardiovascular disease.1

Khan and colleagues designed the PREVENT equations, which they derived from and externally validated in more than 6.6 million US adults (mean age 53 years; 56% women) from 50 distinct data sets to ensure representation from diverse racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, and geographic backgrounds.2

The incorporation of kidney and metabolic risk factors into the new CVD risk estimation algorithm followed directly from the AHA’s recent defining of cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic (CKM) syndrome. Naming CKM acknowledges the increasing prevalence of metabolic and kidney disease and their significant overlap with other conditions in the pathophysiology of CVD. The new CVD risk equations account for the escalating risk of MI, stroke, or HF at successive stages of CKM.

In addition to traditional metrics like blood pressure and cholesterol levels, PREVENT also incorporates HbA1c, estimated glomerular filtration rate, tobacco use, medications, age, and sex.

Khan highlighted the tool’s potential to support more accurate assessment of global cardiovascular risk, leading to early interventions that could mitigate risk and retard disease progression. Khan is a preventive cardiologist at Northwestern Medicine and associate professor at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

Notably, PREVENT recognizes the significance of long-term risk estimation, providing predictions for heart attack, stroke, and heart failure over 10 and 30 years for individuals aged 30 to 79 years. The previous calculator assessed individuals 40 years and older, looking only a decade ahead.3

“Longer-term estimates are important because short-term or 10-year risk in most young adults is still going to be low,” Khan said.3 “We wanted to think more broadly and apply a life-course perspective. Providing information on 30-year risk may reveal earlier opportunities for intervention and prevention efforts in younger people.”3

“We also acknowledge that racism, and not race, operates at multiple levels to increase risk [for CVD],” Khan said, noting that more research is needed to identify the exact factors that underlie racial differences in CVD risks and outcomes.3

Khan expressed hope that estimates based on PREVENT formulas will prompt early conversations between health care professionals and patients, fostering awareness of CKM health status and CVD risk.