Health Care, Insight, Symptoms, Treatment

Barrett’s Esophagus: Symptoms, Causes, and Treatments

Barrett’s esophagus is a consequential and potentially serious complication of a medical condition known as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Within the intricate realm of gastroenterology, this condition presents a unique transformation in the esophagus, the muscular tube that facilitates the journey of food from the mouth to the stomach. The hallmark of Barrett’s esophagus is the conversion of the normal esophageal tissue into tissue that remarkably resembles the lining of the intestine. Although the symptoms of Barrett’s esophagus are not unique in themselves, the paramount concern lies in the escalated risk of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma, a formidable and potentially fatal cancer affecting the esophagus.

This exploration will delve into the intricate facets of Barrett’s esophagus, its relationship with GERD, the diagnostic methodologies employed, treatment approaches, and the need for vigilance in its management. The aim is to provide comprehensive information and insights into this condition that affects a significant segment of the population.

Understanding GERD and Its Connection to Barrett’s Esophagus

GERD is characterized by symptoms such as heartburn, a sour, burning sensation in the back of the throat, chronic cough, laryngitis, and nausea. It is essential to grasp how GERD operates in the context of Barrett’s esophagus. When individuals ingest food or liquids, these substances traverse through the esophagus, a hollow and muscular tube connecting the throat to the stomach. The lower esophageal sphincter, a ring of muscle located at the juncture of the esophagus and the stomach, serves as a vital barrier, preventing the upward flow of stomach contents into the esophagus.

The stomach is designed to generate acid for the purpose of digesting food, but it is inherently shielded from the corrosive effects of the acid it produces. In the case of GERD, the natural order is disrupted, leading to the backward flow of stomach contents into the esophagus, a phenomenon known as reflux.

It’s important to note that not all individuals with acid reflux develop Barrett’s esophagus, and conversely, not all cases of Barrett’s esophagus are linked to GERD. However, long-standing GERD remains the primary risk factor associated with the development of Barrett’s esophagus. While Barrett’s esophagus can affect anyone, white males with a history of persistent GERD are at higher risk, as are those who experienced the onset of GERD at a young age and individuals with a history of smoking.

The Diagnosis of Barrett’s Esophagus

Barrett’s esophagus is often an inconspicuous condition, devoid of specific symptoms. Consequently, its diagnosis relies on specific medical procedures. The American Gastroenterological Association recommends screening for Barrett’s esophagus in individuals possessing multiple risk factors, such as being over 50 years of age, male, of white race, having a hiatal hernia, enduring prolonged GERD, and being overweight, especially with a tendency to carry excess weight around the midsection.

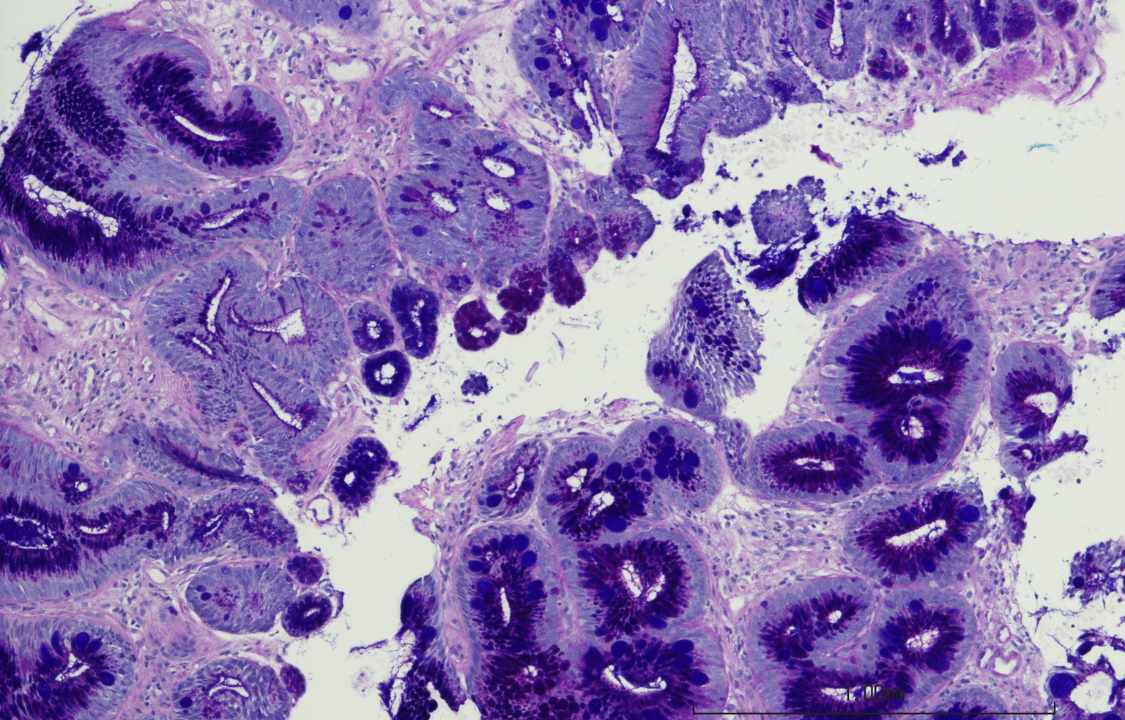

The pivotal diagnostic procedure is an upper endoscopy, coupled with a biopsy. During an endoscopy, a gastroenterologist, a specialized doctor in gastrointestinal disorders, introduces a flexible tube with an attached camera through the throat into the esophagus, with the patient under sedation. While the procedure may induce some discomfort, it is generally not painful. The endoscope allows the doctor to visually inspect the esophageal lining, with Barrett’s esophagus being observable on the camera. However, a definitive diagnosis necessitates the extraction of a small tissue sample, which is subsequently subjected to microscopic examination in a laboratory.

In addition to confirming the presence of Barrett’s esophagus, the biopsy enables the identification of precancerous cells or cancer. If the biopsy affirms the existence of Barrett’s esophagus, the medical professional is likely to recommend periodic follow-up endoscopies and biopsies to detect early signs of cancer development, as the disease’s progression can be gradual.

Treatment Strategies for Barrett’s Esophagus

One of the primary objectives in managing Barrett’s esophagus is to prevent or impede its progression through the effective control of acid reflux. This involves a combination of lifestyle modifications and pharmacological interventions. Lifestyle adjustments include:

1. Dietary Modifications: Eliminating or reducing the consumption of trigger foods like fatty foods, chocolate, caffeine, spicy foods, and peppermint, which can exacerbate reflux.

2. Avoidance of Aggravating Substances: Abstaining from alcohol, caffeinated beverages, and tobacco is crucial, as these substances can intensify GERD.

3. Weight Management: Addressing excess weight is pivotal, as obesity heightens the risk of reflux. Losing weight can be instrumental in symptom management.

4. Elevating the Head of the Bed: Sleeping with the head of the bed elevated is a practical measure that may prevent the upward flow of stomach acid into the esophagus.

5. Post-Meal Resting: Avoiding lying down for at least three hours after meals is advisable.

6. Medication Management: Taking medications with a copious amount of water is important for the optimal effectiveness of the prescribed drugs.

Pharmacological interventions encompass:

1. Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs): These medications are employed to curtail the production of stomach acid, aiding in acid reflux control.

2. Antacids: These substances work to neutralize stomach acid, offering relief from the symptoms of reflux.

3. H2 Blockers: H2 blockers diminish the release of stomach acid, further contributing to symptom relief.

4. Promotility Agents: These drugs expedite the transit of food from the stomach to the intestines, reducing the likelihood of reflux.

Tailored Treatments for Barrett’s Esophagus

In cases where Barrett’s esophagus is established, specific treatments are designed to target the abnormal tissue. These treatments include:

1. Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA): RFA employs radio waves administered through an endoscope inserted into the esophagus to eliminate abnormal cells while safeguarding healthy tissue beneath.

2. Photodynamic Therapy (PDT): PDT uses a laser through an endoscope to eliminate abnormal cells in the esophageal lining without causing harm to normal tissue. Prior to this procedure, patients are administered a light-sensitive drug, Photofrin.

3. Endoscopic Spray Cryotherapy: This innovative technique employs cold nitrogen or carbon dioxide gas through an endoscope to freeze and destroy the abnormal cells.

4. Endoscopic Mucosal Resection (EMR): EMR involves the elevation and removal of the abnormal lining from the esophageal wall through an endoscope. The objective is to eliminate any precancerous or cancer cells within the lining. In cases where cancer cells are detected, an ultrasound examination is conducted to assess whether the cancer has infiltrated deeper layers of the esophagus.

5. Surgical Intervention: In scenarios where severe precancerous or cancerous lesions are diagnosed, surgery to excise a significant portion of the esophagus may be considered. The timeliness of the surgical intervention significantly impacts the prospects for a cure.

It is essential to keep several fundamental facts in mind:

1. Prevalence of GERD: GERD is a common ailment among adults in the United States.

2. Risk of Barrett’s Esophagus: A relatively small proportion of individuals with GERD, less than one in ten, progress to develop Barrett’s esophagus.

3. Risk of Esophageal Cancer: The annual conversion rate of Barrett’s esophagus to esophageal cancer is less than 1%.

While a diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus is not a cause for immediate alarm, it underscores the importance of collaborating closely with healthcare providers to maintain vigilance over one’s health. Routine monitoring and management can significantly enhance the quality of life for individuals grappling with this condition, thereby reducing the risk of its progression to more severe stages.