Infection

Bleach does not tackle fatal hospital superbug, UK researchers find

Liquid bleach does not kill off a hospital superbug that can cause fatal infections, researchers have found.

The researchers say new approaches are needed towards disinfection in care settings.

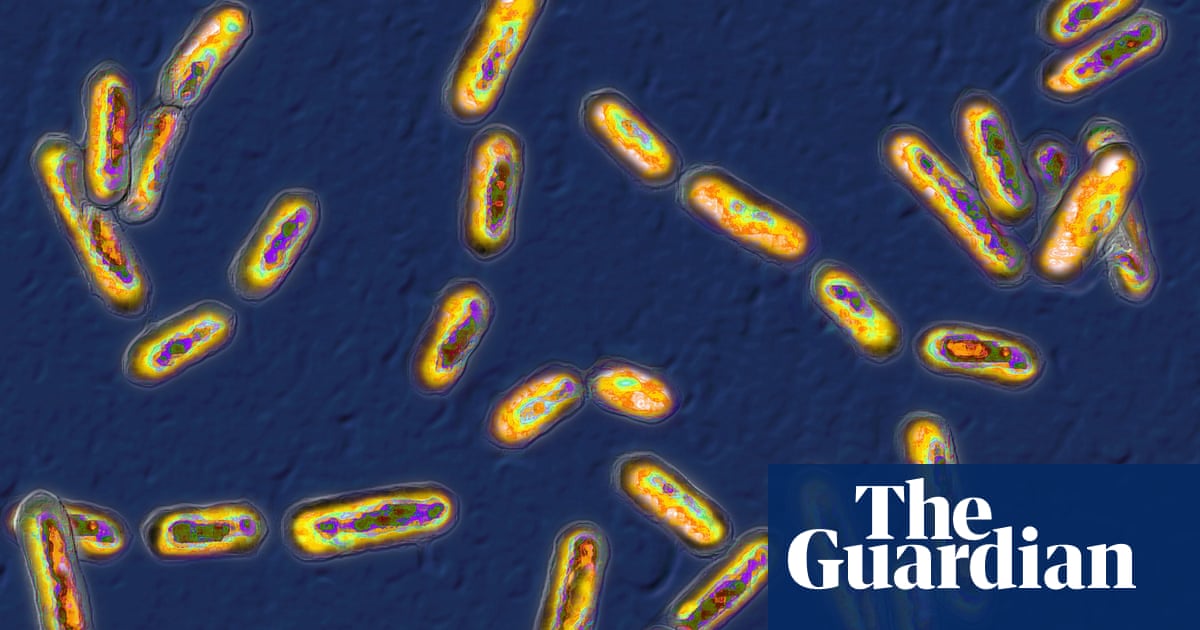

Clostridium difficile, also known as C diff, is a type of bacteria found in the human gut. While it can coexist alongside other bacteria without problem, a disruption to gut flora can allow C diff to flourish, leading to bowel problems including diarrhoea and colitis.

Severe infections can kill, with 1,910 people known to have died within 30 days of an infection in England during financial year 2021-2022.

Those at greater risk of C diff infections include people aged over 65, those who are in hospital, people with a weakened immune system and people taking antibiotics, with some individuals experiencing repeated infections.

According to government guidance, updated in 2019, chlorine-containing cleaning agents with at least 1,000 ppm available chlorine should be used as a disinfectant to tackle C diff.

But researchers say it is unlikely be sufficient, with their experiments suggesting that even at high concentrations, sodium hypochlorite – a common type of bleach – is no better than water at doing the job.

“With antimicrobial resistance increasing, people need to recognise that overuse of biocides can cause tolerance in certain microbes, and we’re seeing that definitely with chlorine and C diff,” said Dr Tina Joshi, co-author of the research, from the University of Plymouth.

While chlorine-based chemicals used to be effective at killing such bacteria, that no longer appears to be the case, she said.

“The UK doesn’t seem to have any written new gold standard for C diff disinfection. And I think that needs to change immediately,” she said.

Writing in the journal Microbiology, Joshi and colleagues report how they exposed spores from three different strains of Clostridium difficile to three different concentrations of sodium hypochlorite bleach – ranging from 1,000 ppm to 10,000 ppm. The spores were left for 10 minutes before the bleach was neutralised.

The researchers then attempted to culture the spores on agar plates, and compared the results with the controls of spores exposed only to water or the neutralising substance.

after newsletter promotion

The results reveal spores from all three strains of C diff survived all three concentrations of bleach, with no significant reduction in their ability to germinate compared with the controls. Indeed, scrutiny of the spores with scanning electron microscopy showed that they underwent no visible damage when exposed to the cleaning agent.

The researchers also applied spores of C diff to squares of fabric cut from new multiuse surgical scrubs and patient gowns and tested whether they would transfer when an agar plate was touched by the fabric.

The team found the spores largely remained on the gowns and scrubs, with exposure of the spores to different concentrations of bleach making no tangible difference.

“It’s very clear that the spores are sticking to the fibres,” said Joshi, noting that that finding suggests such items are reservoirs of transmission.

Joshi said the new work has important implications. “Even if we’re trying to disinfect across different surfaces, the chlorine is not doing its job,” she said. “It’s not the right biocide.”