Infection

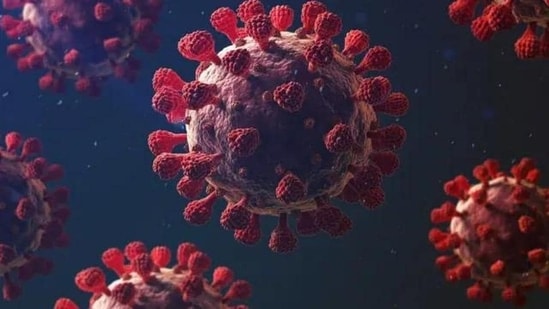

High levels of exposure to Covid virus may reduce protection from vaccination, prior infection: Study

The study tried to understand whether immunity gained after vaccination or a prior infection was less effective or “leaky” when people are exposed to the virus.

High levels of exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 virus may reduce or overcome the protection that COVID-19 vaccination and prior infection provides, according to a study conducted in the US. (Also Read | How the COVID pandemic changed the travel industry)

The findings, published recently in the journal Nature Communications, suggest that in densely crowded settings, control measures that reduce levels of exposure to the virus — such as masking, improved ventilation, and distancing — may afford additional benefit in preventing new infections among people who have been vaccinated or previously infected.

The study was performed to understand whether the immunity gained after vaccination or a prior infection was less effective or “leaky” in situations where people are exposed to high levels of the virus.

“It’s really hard to find a population, such as the residents of the Connecticut Department of Correction, where we know the type of exposure somebody has and we know their vaccination and prior infection status,” said Margaret Lind, lead author of the research paper, and an associate research scientist at Yale University, US.

The researchers tracked infections among 15,444 residents of Connecticut correctional facilities between June 2021 and May 2022, when the state experienced two epidemic waves due to the emergence of the COVID-19 Delta and Omicron variants.

They also determined which people had resided with a COVID-19-positive cellmate and, as a result, had high exposure to the COVID-19 virus.

The study found that during the Delta and Omicron epidemic waves, immunity acquired after a vaccination, prior infection, and both vaccination and infection (hybrid immunity) was weaker when residents were residing with an infected inmate.

Specifically, during the Delta wave, vaccination was 68 per cent effective at preventing infection in residents without a documented exposure but was just 26 per cent effective in residents with exposure to an infected cellmate, the researchers said.

A previous infection was 79 per cent effective in preventing infection in residents without a documented exposure but was 41 per cent effective when a resident was exposed to an infected person in their cell, they said.

Hybrid immunity provided the highest level of protection, at 95 per cent and 71 per cent effectiveness, in residents without a documented exposure and with a cell exposure, respectively, according to the researchers.

While the overall protection afforded by vaccination, prior infection, and hybrid immunity was lower during the epidemic wave with the more-transmissible Omicron variant, the same pattern in the levels of protection was observed, they said.

The researchers also found that vaccination was 43 per cent effective at preventing infection in residents without documented exposure but was just 4 per cent in residents who shared a cell with an infected person.

A previous infection was 64 per cent effective without a documented exposure but was only 11 per cent effective when a resident was exposed to an infected person in their cell.

Although hybrid immunity afforded higher levels of protection during the Omicron wave, it was only 20 per cent effective in residents with an exposure in their cell as compared to being 76 per cent effective in residents without documented exposure.

“This research is the first study, as far as we are aware, that provides real-world evidence for the exposure-dependent or ‘leaky’ nature of the immunity afforded by vaccination and infection,” Lind added.

This story has been published from a wire agency feed without modifications to the text.