Infection

Long COVID research: A pre-pandemic common cold coronavirus infection could explain why some patients develop long COVID

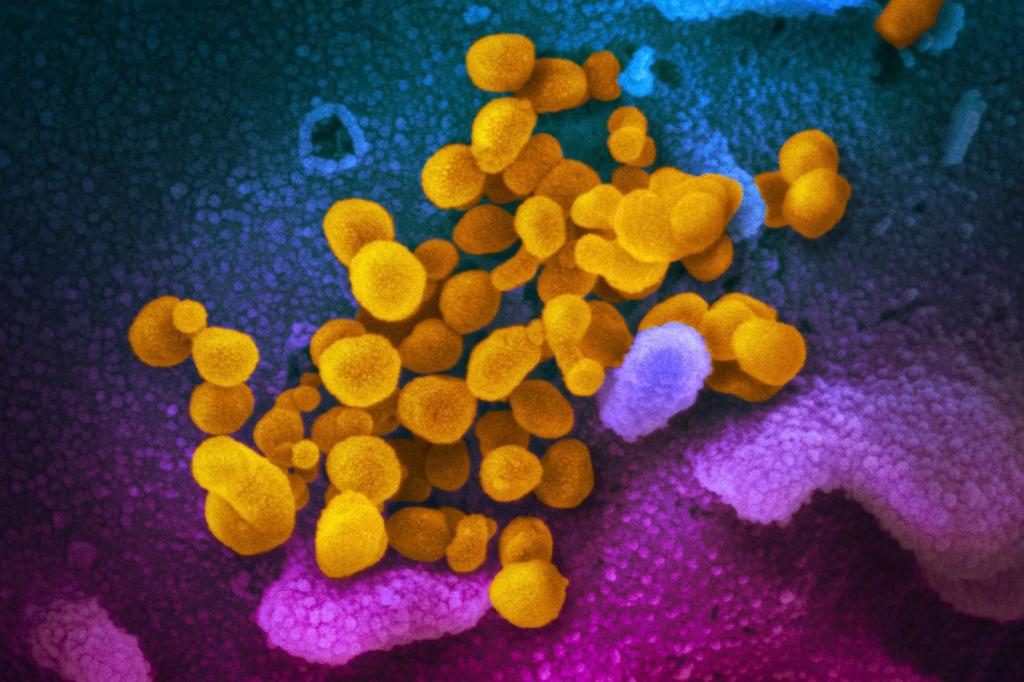

A pre-pandemic common cold coronavirus infection may help set the stage for long COVID, according to Boston researchers who have been looking to explain why some patients end up facing the long-lasting, debilitating symptoms.

The researchers from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital teamed up with experts in immunology and virology to look for clues about long COVID in blood samples from patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases.

The team found that among these patients, those who developed long COVID were more likely to have expanded, pro-inflammatory antibodies specific to a coronavirus that causes the common cold.

A person’s viral history, especially prior infection and expansion of antibodies against a pre-pandemic coronavirus, could prime the immune system for developing long COVID, according to the researchers.

“Our study offers evidence and explanation for why some of our patients may be experiencing the persistent and wide-ranging symptoms of long COVID,” said co-corresponding author Zachary Wallace, of the Division of Rheumatology, Immunology and Allergy at Massachusetts General Hospital.

“Identifying a biomarker that helps us better understand current and previous infections could shed light on an inappropriate immune response that leads to some cases of long COVID,” Wallace added.

Up to 45% of individuals with rheumatic diseases — which include rheumatoid arthritis and other chronic autoimmune disorders that cause inflammation — experienced persistent symptoms associated with long COVID 28 days after acute infection with SARS-CoV-2.

Patients with rheumatic diseases are also at risk for more severe disease and complications from acute infection.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, the Brigham and MGH researchers have paid special attention to this group of patients to help with long COVID treatments and care.

The researchers compared immunological changes in patients with rheumatic diseases who recovered from COVID. Specifically, they looked for differences in the immunological fingerprints left behind by previous infections.

The team found an unexpected signal tied to OC43, a coronavirus that causes common cold symptoms. Individuals with long COVID were more likely to have antibody responses specific to this form of coronavirus.

The study is restricted to individuals with rheumatic diseases, and further research is needed to determine if their findings will apply more widely to patients without a pre-existing autoimmune disorder.

“By starting with patients with rheumatic diseases, we may be able to develop biomarkers that help us understand who is at high risk for developing long COVID and strategically enroll individuals into clinical trials to either prevent long COVID or develop therapies to treat it,” said Wallace. “This study represents an important step in that direction.”