Brain, Disease, Infection, Inflammation

What Causes Meningitis? These Infections, Injuries, and Substances May Be to Blame

Several types of bacteria and viruses are common culprits.

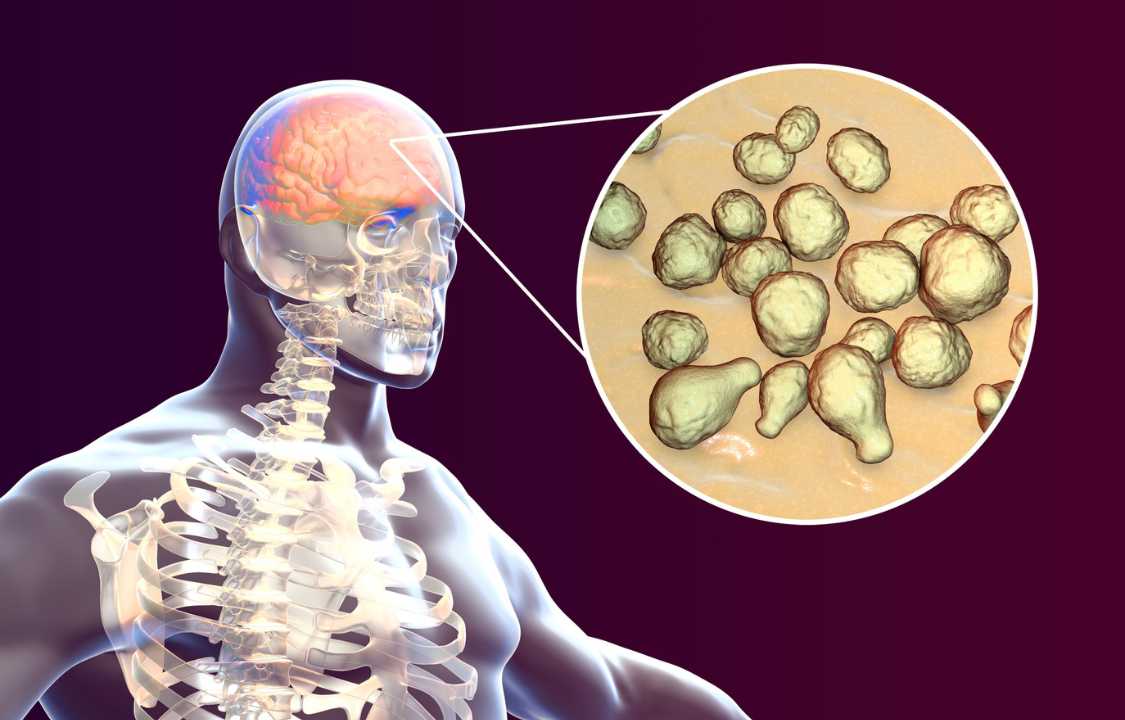

Meningitis is a potentially life-threatening condition characterized by the inflammation of the meninges, the protective membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord. While bacterial meningitis is a well-known cause of this infection, it’s crucial to recognize that various agents, injuries, and infections can trigger this serious medical condition. Meningitis affects approximately 2.5 million people worldwide each year, as reported by the World Health Organization, making it a significant global health concern. Understanding the diverse causes of meningitis is vital for proper diagnosis, treatment, and prevention.

Meningitis and Its Causes

The term “meningitis” itself refers to the swelling or inflammation of the meninges. These membranes play a vital role in shielding the brain and spinal cord from harm, providing cushioning and protection. When the meninges become inflamed, whether due to infectious agents, injuries, or other factors, a range of symptoms can manifest. These symptoms often include a severe headache, high fever, sensitivity to light (photophobia), nausea, vomiting, joint pain, a distinctive rash, and a stiff neck that restricts the ability to move the head or touch the chin to the chest.

In the early stages, the symptoms of meningitis can resemble those of the flu, making it challenging to diagnose accurately. Depending on the underlying cause, these symptoms can develop rapidly, sometimes escalating within a matter of hours. As a result, public health agencies, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), recommend vaccinations against certain types of bacteria that can cause meningitis, particularly for preteens, teens, and even some children and adults. However, it’s important to note that vaccines only provide protection against specific bacterial strains responsible for meningitis.

Diverse Causes of Meningitis

Beyond bacteria, several other factors and agents can lead to meningitis. These include:

1. Viruses: Viral meningitis is a common form of the condition. It can be caused by various viruses, with non-polio enteroviruses being a prevalent culprit in the United States. Other viruses known to trigger viral meningitis include herpesviruses, Epstein-Barr virus, herpes simplex viruses, varicella-zoster virus, mumps virus, measles virus, influenza virus, arboviruses, and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus.

2. Parasites: Parasitic meningitis is a less common but notable cause of the infection. Certain parasites, such as Angiostrongylus cantonensis, Baylisascaris procyonis, and Gnathostoma spinigerum, have been linked to meningitis. These parasites are typically contracted through the ingestion of contaminated food or exposure to infected animals.

3. Amoeba: Amebic meningitis is a rare yet exceptionally severe form of the condition. It is primarily caused by the amoeba Naegleria fowleri. Infection occurs when water contaminated with this amoeba enters the nasal passages, leading to a rapid and often fatal progression of symptoms. Due to its rarity and high fatality rate, prevention is of utmost importance.

4. Cancers: In some cases, meningitis can arise as a complication of cancer. Tumors that affect the central nervous system or metastasize to the meninges can lead to inflammation and the development of meningitis-like symptoms.

5. Lupus: Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), an autoimmune disease, can also cause aseptic or non-infectious meningitis as a result of the body’s immune system mistakenly attacking the meninges.

6. Certain Medications: Specific medications, especially those used in treating autoimmune disorders or infections, can trigger aseptic meningitis as a rare side effect.

7. Head Injuries: Traumatic head injuries can disrupt the protective barriers of the brain and spinal cord, potentially allowing bacteria or other agents to enter and cause meningitis.

8. Brain Surgery: Surgical procedures involving the brain or spinal cord carry a risk of postoperative meningitis, particularly if infection control measures are not rigorously followed.

Bacterial Meningitis: A Life-Threatening Emergency

Bacterial meningitis is undoubtedly one of the most dire forms of this condition, necessitating immediate medical intervention. Dr. Marie Grill, a specialist in neuroinfectious diseases at the Mayo Clinic, underscores the urgency of this matter, emphasizing that “getting evaluated promptly and getting proper treatment initiated right away is critical.” Bacterial meningitis arises when bacteria infiltrate the bloodstream and subsequently invade the brain and spinal cord.

The Meningitis Research Foundation reports that there exist at least 50 types of bacteria capable of causing meningitis. The CDC enumerates some of the leading culprits in the United States, including:

1. Streptococcus pneumoniae: This bacterium causes pneumococcal meningitis.

2. Group B Streptococcus: A common cause of meningitis, particularly in newborns.

3. Neisseria meningitidis: Responsible for meningococcal meningitis.

4. Haemophilus influenzae: The perpetrator behind H. influenzae meningitis.

5. Listeria monocytogenes: This bacterium can lead to listeria, which, in turn, may culminate in meningitis.

6. Escherichia coli: Responsible for most cases of E.coli meningitis in infants less than three months old.

The entry points for bacteria to infiltrate the body and incite bacterial meningitis are manifold. They can encompass respiratory secretions, person-to-person contact, and even contaminated food. Dr. Grill further elucidates that injuries or infections in proximity to the brain, such as ear infections or dental abscesses, can also set the stage for the onset of bacterial meningitis.

Once bacteria have gained access to the bloodstream, they release toxins that weaken the body’s capillaries. This weakening allows blood to escape, giving rise to what appears as a rash beneath the skin. Dr. Grill clarifies that the presence of such a rash, characterized by reddish-purple spots, triggers immediate concerns about the possibility of meningococcal meningitis. In some instances, certain types of bacterial meningitis may escalate into septicemia, a severe condition commonly referred to as blood poisoning. Septicemia necessitates emergency medical attention as bacteria proliferate in the bloodstream, wreaking havoc and causing substantial damage.

While bacterial meningitis can potentially affect anyone, the CDC highlights certain populations at a heightened risk. These include infants, individuals residing in group settings like college campuses, patients with specific medical conditions such as HIV or cerebrospinal fluid leaks, individuals undergoing particular medications or surgical procedures, as well as microbiologists who work closely with bacteria associated with meningitis. Moreover, travelers to regions of sub-Saharan Africa or crowded pilgrimage destinations like Mecca during peak times are also cautioned regarding potential risks.

The treatment protocol for bacterial meningitis typically involves hospitalization and the administration of antibiotics. Swift diagnosis and intervention are vital in mitigating the severity of bacterial meningitis and reducing the likelihood of long-term complications.

Viral Meningitis: An Intriguing Twist

Viral meningitis, as the name suggests, is instigated by viruses rather than bacteria. In the United States, non-polio enteroviruses dominate as the primary causative agents of viral meningitis, according to the CDC. Dr. Frank Esper, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s Hospital, explains that these viruses, although primarily respiratory in nature, possess the capability to infiltrate the brain and induce inflammation.

Enteroviruses are generally considered less virulent, and cases of viral meningitis attributed to them are often less severe and rarely fatal. The CDC identifies several other viruses that can also trigger viral meningitis, including herpesviruses, Epstein-Barr virus, herpes simplex viruses, varicella-zoster virus (the source of chickenpox and shingles), mumps virus, measles virus, influenza virus, arboviruses (viruses transmitted by certain insects like mosquitoes), and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, which is derived from rodents.

Viral meningitis is generally categorized as non-life-threatening, and most individuals recover without specific treatment within a period of 10 days or less, as indicated by the CDC. Nevertheless, it is imperative to acknowledge that severe cases can arise, necessitating hospitalization and intensive care.

Fungal Meningitis: A Less Common Intruder

Fungal meningitis emerges when a fungal infection originating in another part of the body gains access to the brain or spinal cord. Cryptococcus neoformans stands as one of the principal culprits responsible for fungal meningitis, particularly affecting individuals with weakened immune systems due to conditions such as cancer and HIV. Additionally, other fungal causes include candida albicans, the fungus notorious for causing thrush and yeast infections, and histoplasma, a fungus primarily found in soil enriched with substantial quantities of bird or bat feces. Inhaling the spores of this fungus can lead to a lung infection that subsequently spreads to the brain or spinal cord.

Fungal meningitis, while possible for anyone to contract, is relatively rare. Claire Wright of the Meningitis Research Foundation notes that individuals with compromised immune systems are generally more susceptible to developing this form of meningitis. Symptoms of fungal meningitis can often present in a less acute manner compared to other types of the disease. Dr. Grill explains, “Most people will have headaches that have been going on for weeks even before that is diagnosed because it’s a chronic infectious process for the most part.”

Treatment for fungal meningitis predominantly revolves around the administration of high doses of antifungal medications delivered intravenously, followed by oral versions of these drugs, according to the CDC. The duration of treatment varies, contingent upon an individual’s overall immune status and the specific fungus responsible for the meningitis.

Parasitic Meningitis: An Intriguing Niche

Parasitic meningitis is a rare and intriguing subset of the condition, associated with specific parasites that include Angiostrongylus cantonensis, Baylisascaris procyonis, and Gnathostoma spinigerum, among others. These parasites are typically linked to animal infections, but in unique circumstances, they can afflict humans. Human exposure primarily occurs through the ingestion of contaminated food or animal products.

One distinctive form of parasitic meningitis is eosinophilic meningitis, which stems from consuming undercooked snails, shellfish, crabs, lizards, frogs, raw freshwater fish, eels, poultry, or snakes harboring the responsible parasites. This condition is particularly relevant in certain geographic regions, especially Southeast Asia, as well as among travelers to these destinations. Dr. Grill underscores the consideration of parasites as potential causes for individuals with a history of international travel.

Regrettably, there exists no specific treatment for eosinophilic meningitis beyond symptom management, as reported by the CDC. The unique nature of parasitic meningitis and its relatively infrequent occurrence pose significant challenges in developing standardized treatment protocols.

Amebic Meningitis: A Lethal Intruder

Amebic meningitis, a formidable but exceptionally rare form of the condition, is attributed to the amoeba Naegleria fowleri. This amoeba can be found in soil and warm freshwater sources worldwide. Infection typically occurs when contaminated water enters the nasal passages during activities such as swimming or submerging one’s head during religious rituals. It can also be contracted if an individual irrigates their nasal passages with tap water contaminated by the amoeba.

Despite its rarity, amebic meningitis is often fatal, underscoring the critical importance of prevention. The CDC documented a total of 148 cases in the United States from 1962 to 2019, averaging no more than eight cases annually. Treatment options are limited, and the effectiveness of available medications remains uncertain due to the severity of this form of meningitis.

Non-Infectious Meningitis: Unusual Yet Notable

While uncommon, it is imperative to recognize that meningitis can occasionally arise from non-infectious factors. Dr. Frank Esper elucidates, “It’s an inflammation, but it’s not being caused by a germ.” Instead, non-infectious meningitis is provoked by alternative factors, typically medications, tumors, malignancies, vaccines, head injuries, or brain surgery.

Non-infectious meningitis can present with symptoms akin to other forms of the condition, such as headaches, fever, and a stiff neck. However, in some instances, the symptoms may be less severe and evolve more gradually.

Treatment for non-infectious meningitis hinges on identifying the underlying cause. In cases where the cause remains ambiguous, preventive antibiotics may be initiated until cerebrospinal fluid analysis and further diagnostic measures ascertain the trigger. If the causative factor is a medication, it is typically discontinued.

In conclusion, the comprehensive understanding of the diverse causes of meningitis is pivotal in enhancing our ability to diagnose, treat, and prevent this serious medical condition. From bacterial meningitis demanding immediate antibiotic intervention to viral meningitis often self-limiting but requiring vigilant monitoring, fungal meningitis necessitating prolonged antifungal therapy, parasitic meningitis associated with unique sources of exposure, amebic meningitis as a rare yet lethal intruder, to non-infectious meningitis stemming from alternative triggers, each subtype demands tailored approaches to patient care. Through enhanced awareness, research, and preventive measures, we can strive to mitigate the impact of meningitis and improve outcomes for affected individuals worldwide.