Blood

Marine worm haemoglobin could be the new frontier of blood doping

The use of lugworm haemoglobin could become the latest blood doping technique to be used in professional cycling, with its creator Dr. Franck Zal revealing to l’Equipe that in 2020, a “well-known cyclist whose team participates in the Tour de France, contacted me because he wanted the product”.

Anti-doping blood tests can detect the ‘super haemoglobin’ but it is easy to use and its short half life means it becomes undetectable after just a few hours. Its use is unlikely to be spotted in an athlete’s Biological Passport.

There have been few blood doping cases in professional cycling in recent years thanks to the Biological Passport and a recognised change in attitude in the peloton.

Arenicola marina lugworms, also known as sandworms, are commonly used as fishing bait, but Dr. Zal helped create Arenicola marina lugworm extracellular haemoglobin for medical use after discovering the worm’s incredible oxygen transporting qualities. Lugworms can live both underwater and in the air.

The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) have insisted to l’Equipe that no cases of lugworm haemoglobin doping have been detected but are concerned about its use as a powerful blood doping technique.

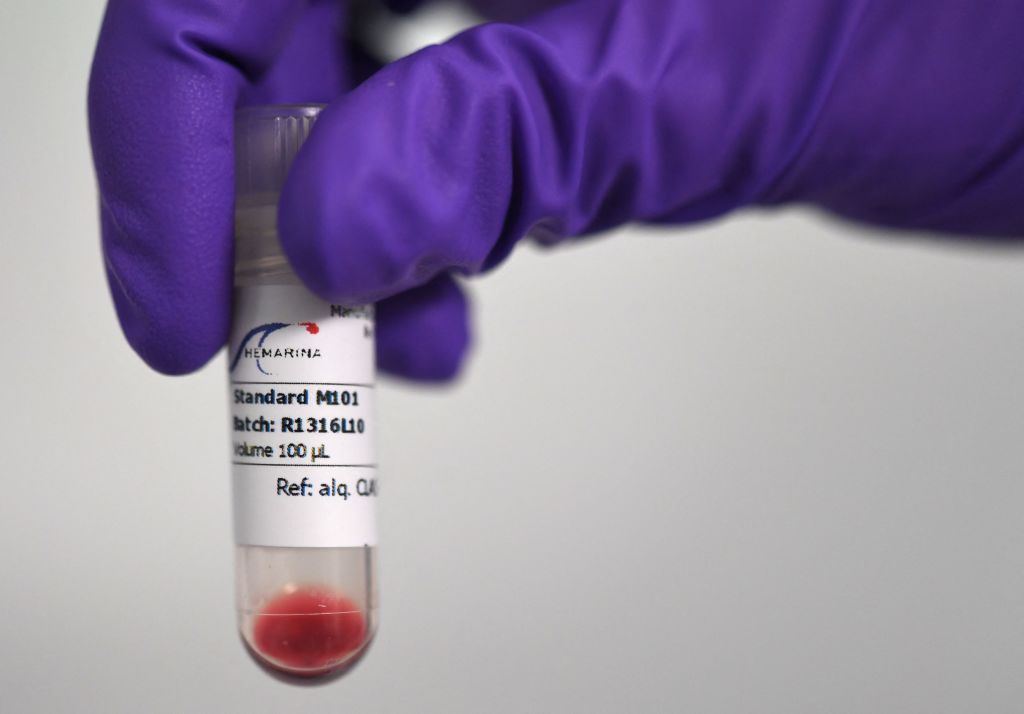

Dr. Zal patented his discovery and created the Hemarina company, that has its own worm farm on the Island of Noirmoutier in the Vendée region of France. Hemarina calls the Arenicola marina lugworm extracellular haemoglobin M101, claiming it has been perfected by 450 million years of evolution.

Hemarina claims lugworm haemoglobin is a universal blood substitute that can transport 40 times more oxygen than human haemoglobin. It is 250 times smaller than other red blood cells, which helps circulation. It is compatible with all blood groups, doesn’t increase blood hematocrit or cause high blood pressure like bovine or human haemoglobin. It can be stored at room temperature and freeze-dried, making it easy to transport.

Hermarina have created a number of specific products with lugworm haemoglobin, including the HEMOXYCarrier universal oxygen carrier, a solution to help preserve organs used for transplants, oxygenated dressings, cell growth activation and even fermentation for cheese wine and bread yeast.

The HEMO2life additive to help organ transplantation has recently been approved for medical use in Europe, making it readily available.

Dr. Zal discovered lugworm haemoglobin in 2007 and quickly realised his products could become a target for blood dopers, even if they are created to save lives.

“I understood very early on that it could be diverted,” he told l’Equipe. “We had several direct requests from athletes or gyms, who wanted to know how to obtain the substance. I also learned of its possible administration to racehorses.”

Dr. Zal says the well-known cyclist contacted him in July 2020 as riders prepared for the rescheduled COVID-19 pandemic season in the second half of the year. He quickly told the French OCLAESP police that work to protect public health.

“I asked them what to do, they replied: ‘Make him talk, we want to see if there is a network.’ We had around ten exchanges of emails but at some point, I told myself that it’s their job, not mine,” Dr Zal revealed.

The OCLAESP confirmed the discussions to l’Equipe but refused to give further details.

Dr. Zal revealed he had already helped the OCLAESP when a form of powered haemoglobin was discovered during the Operation Aderlass investigation in Germany.

Aderlass exposed the use of pre-race micro blood transfusions in nordic skiing and other doping techniques. Mark Schmidt, the doctor at the heart of the Aderlass blood doping ring, was sentenced to four years and 10 months in prison in 2021. Alessandro Petacchi, Danilo Hondo, Georg Preidler, Borut Bozic, Kristijan Koren and Kristijan Durasek were implicated in the case and handed bans from the sport of varying lengths.

The Cycling Anti-doping Foundation carried out the reanalysis of 800 in-and out-of-competition blood and urine samples after Operation Aderlass but the CADF said none discovered a haemoglobin-based oxygen carrier (HBOC). HBOC are banned under the WADA anti-doping code but the lugworm haemoglobin is difficult to detect due to its very short half-life.

Any anti-doping blood tests would have to be taken immediately after races with a threshold for the banned substance also a possible problem. Blood samples are often taken from race winners and race leaders after races but usually only an hour or so after the finish and podium obligations.

Anti-doping rules now allow for testing during the night when justified and some teams underwent surprise anti-doping blood tests just an hour before the start of some races in 2023.

“Sea worm haemoglobin works very quickly in the body after injection but it also has a very short lifespan,” Adeline Molina of the L’Agence française de lutte contre le dopage (AFLD) told l’Equipe. “This is a product to look for in competition. But it is visible in a blood test.”

Recent research published by Analytical Science Journals into the detection of extracellular haemoglobin from Arenicola marina in doping control serum samples suggested that “a detection window of 4–8 h should be sufficient to uncover doping with lugworm Hb. However, no data on the administration of M101 to humans have been published so far, so the results of this study still need to be confirmed in human subjects.”

The research concluded that: “Due to its promising therapeutic properties, lugworm Hb represents an emerging doping agent which can potentially be misused in sports to improve the oxygen delivery capacity of the blood.

“Even though clinical approval for in vivo use as oxygen carrier is still missing, a graft preservative for transplant procedures containing lugworm Hb as active ingredient M101 has recently obtained the CE marking allowing its marketing as medical device for ex vivo usage in Europe, which makes the drug readily available for cheating athletes.”

WADA told l’Equipe they are aware of the risks of lugworm haemoglobin being used for blood doping.

“There was a very rapid understanding of this substance and its risks for doping purposes. We bought the product and put it in the hands of the anti-doping laboratories,” Professor Olivier Rabin, scientific director of the WADA said.

“If this substance had been found in an athlete, we would have made it public,” Rabin added. “I can’t guarantee that this hasn’t happened somewhere in the world. But to my knowledge, this is not the case.”