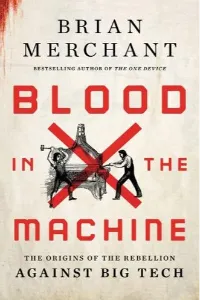

Blood

Blood in the Machine: The Origins of the Rebellion Against Big Tech

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

For those who use it as an invective, “Luddite” is particularly handy: it casts opposition to technology as not just futile but cult-like. Luddites aren’t merely irrational; they’re weird and obsessive.

This is partly a side-effect of the inventive mythmaking deployed by the original machine-wrecking Luddites of the early 19th century. This involved secret handshakes, gruesome animal-skin masks and much else besides. In some ways, these rituals were very much in keeping with the temper of the times (the period was chock-full of secret societies).

Yet as Brian Merchant explains in Blood in the Machine, the Luddites’ leaderless spontaneity was actually more thought-through — and much more significant — than their reputation would suggest.

A technology columnist for The Los Angeles Times, Merchant’s first book was 2017’s The One Device, an alternative look at the development of the iPhone. In this book he goes further, with a provocative rehabilitation of the Luddites as a well-organised labour movement who nearly incited a civil war. Above all, though, Merchant seeks to draw links between the spirit of the Luddites and the recent backlash against Silicon Valley.

The Luddite unrest began in 1811, when factory owners in Nottingham began using new labour-saving devices such as the gig mill — used in the production of fabric — as a means of cutting jobs and wages. Merchant notes that textile workers had already embraced some forms of mechanisation, but soon found themselves on the sharp end of the Industrial Revolution. Lacking political recourse, the textile workers responded in the only way they felt would get their point across: by waiting until dark, breaking into the factories and destroying the machines.

Although sabotage was confined to the burgeoning industrial heartlands of northern England, it operated in tandem with political lobbying, including strong support from poet Lord Byron. The Luddites also published foreboding letters under the name of “General Ludd” — a fictional figurehead for their movement. And in one of the many archival gems recounted by Merchant, male Luddites were known to dress up in drag and march through town, declaring themselves to be “General Ludd’s wives” in an act of solidarity with female cloth workers who had been put out of work by automation decades earlier.

The then prime minister Spencer Perceval responded by sending troops to northern mill towns. The Luddites, meanwhile, stockpiled arms and melted down machine metal for bullets. As a way of getting employers to the bargaining table, their approach was surprisingly successful, bolstering wages and working conditions for textile workers.

More notably, the Luddites’ activities paved the way for the creation of the first trade unions. They also influenced the development of English Romantic thought, changing the conversation around technological progress and very probably providing one inspiration for Mary Shelley’s groundbreaking novel Frankenstein, published in 1818.

At times, Blood in the Machine suffers from the author’s decision to split the historical narrative into truncated, rapid-fire chapters that rotate through a large cast of characters. Reading the book can sometimes feel like getting jerked through a power loom.

Luckily, Merchant’s longer chapters present a more nuanced argument — making parallels between the Luddites to contemporary worker movements at tech companies such as Uber and Amazon. With smart historical digging, he shows how 19th-century entrepreneurs used insecure, casualised employment arrangements, and recreates early debates between factory owners who were dealing with the pressure to automate their operations.

If Merchant occasionally overstates the historical role of the Luddites, he makes up for it by showing that the struggle against technology that dominates our lives is also inherited. Calls to slow the development of human-level artificial intelligence are perhaps the most unexpected modern manifestation of the old Luddite sensibility.

Merchant also uncovers some interesting policy demands by textile workers that are clear precedents for the proposals being put forward in the modern tech industry, including automation phase-ins, retraining and a tax on automated goods. The Luddites didn’t “hate” technology, writes Merchant, but “the way it was used against them” — and they understood its power all too well.

Blood in the Machine: The Origins of the Rebellion Against Big Tech, by Brian Merchant, Little, Brown £25/$30, 496 pages

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café